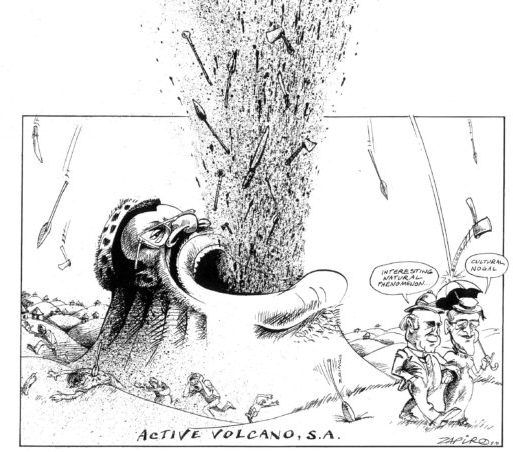

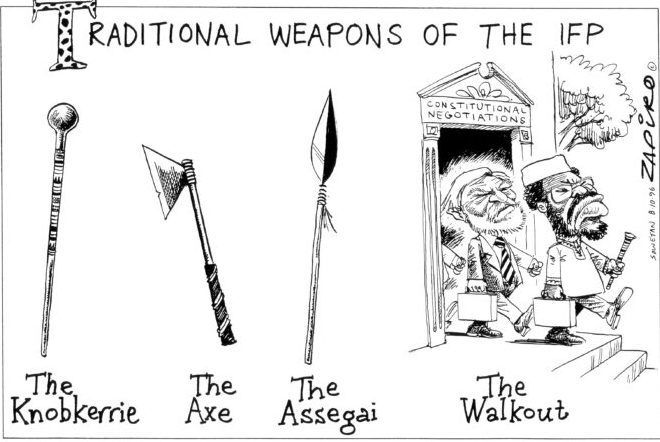

Tribute to Mgiliji Zihogozelanga Nhleko: Mzala Nxumalo continues to haunt Buthelezi from the grave on freedom of expression

Another Book Review By: Chantelle Wyley and Christopher Merrett

In early May 1991 a number of university libraries in South Africa received a letter from attorneys Friedman and Friedman, acting on behalf of Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi, Chief Minister of KwaZulu and President of Inkatha. It noted the fact that libraries possessed and were circulating copies of a book by Mzala (pseudonym of Jabulani Nobleman Nxumalo) entitled Gatsha Buthelezi: Chief with a double agenda...

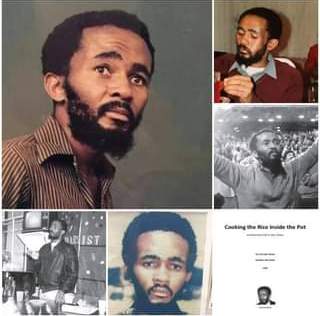

Zihogozelanga 'Mgiliji' Nhleko (left) and Jabulani "Mzala' Nxumalo (right). Both of them fiercely criticized Buthelezi before they died of mysterious 'illnesses' in hospital. Other prominent figures who fiercely criticized him and recently died mysteriously in hospital are King Goodwill Zwelithini Zulu and Zanele ka Magwaza-Msibi. Before publishing this article, Izazi noted that Cyril Ramaphosa has sent condolences to the FW de Klerk family for the death of the last president of the apartheid government, yet no condolences so far has been forthcoming from Buthelezi and Ramaphosa for Nhleko's demise

Chief Buthelezi claimed that the book was defamatory of him and threatened that continued circulation of it would lead to claims for damages. Libraries were required to submit a written undertaking within 14 days that the book had been withdrawn from the shelves and would not subsequently be loaned to any individual or organization.

Gatsha Buthelezi: Chief with a double agenda was published by Zed Books in London in February 1988. The author was an academic and researcher employed by the African National Congress. An "outstanding scholar", Mzala was first detained by the South African authorities for political activity at the age of fifteen.

Involvement in the 1976 students' revolt disrupted his education in the Law Faculty of the University of Zululand, and once in exile, he joined the ANC and later the South African Communist Party. He was stationed in Mozambique, Angola, Swaziland and Tanzania as an ANC representative, and member of the military wing; Umkhonto we Sizwe.

Mzala studied politics in East Germany, and was registered for a doctoral degree on the national question in South Africa with the Open University in Britain. His research and the writing of the Buthelezi biography were conducted in terms of his academic work, and were quite independent of the ANC. After completing the book Mzala began work on a biography of ANC President Oliver Tambo, which was to be the focus of a post-doctoral fellowship year at Yale. In late 1990 however, he fell ill, and died in London on February 22 1991 at the early age of thirty five. He was buried in South Africa.

Mzala's biography of Gatsha Buthelezi is a popular but scholarly work of historical interpretation. He makes forthright points about Buthelezi's political past, his role in South African society, the nature of the KwaZulu administration and the methods of Inkatha.

Nhleko arrives at the Zuma homestead in Nkandla, KwaZulu-Natal to show support for former President Jacob Zuma. This is how he commented after Buthelezi had criticized and expelled him as Amabutho (Zulu regiment leader) for doing so: “Zuma is one of our own and I do not regret the decision to support him. He is part of Amabutho and an attack on Zuma is an assault on AmaZulu as a nation."

Furthermore, he is highly critical of the Chief Minister of the KwaZulu Bantustan's claims to anti-apartheid credibility and to a hereditary leadership position in the Zulu nation. These claims are presented in the academic tradition and are supported by evidence gleaned from historical, documentary and oral sources.

Given the Chief Minister's propensity for litigation, Zed Books had been cautious with the manuscript. Two sets of British lawyers examined the book before publication, and amendments were made on their recommendation. They gave assurances that it was unlikely that the published book would be actionable in terms of the British law of defamation.

Although the South African law is based on British legislation, the publishers were unsure of the attitude of South African judges, who were felt to be system supporting. In any event Zeds agents in South Africa, David Philip Publishers, were subjected to direct threats of a defamation action in the event of local distribution. This intimidation forced the publisher and agents into a decision not to release the book in South Africa.

Nevertheless, university libraries were able to obtain copies ordered via European book distributors and library suppliers and privately-owned copies were widely circulated and photocopied. Some of these came from book stores in South Africa's neighbouring states, and it seems that a flourishing cross-border trade developed.

The ANC had undertaken to assist Zed in distributing the book taking responsibility for about 8 000 copies of the print run of 12 000 Between 1988 and 1990 copies of Chief with a double agenda were brought into South Africa in the backpacks of Umkhonto we Sizwe soldiers. They were prized like gold, and passed from hand to hand in samizdat fashion" - (A system of clandestine printing and distribution of dissident or banned literature).

Despite some of the difficulties involved in obtaining copies of the book, it caused something of a stir, and was reviewed in local publications.

The Chief Minister of KwaZulu was clearly aware of what the book represented. Soon after it was reviewed in Frontline magazine, a letter appeared on its letters page from the Chief Minister's attorneys, indicating that their client considered Chief with a double agenda to be defamatory of him, and that he had instructed them "to institute legal action immediately if the book is distributed in South Africa". Furthermore, their client "refuses further to reply to such a book which he holds in contempt".

It is interesting to note that Chief with a double agenda had never been banned by the South African state, despite the author's association with the ANC; in any event, official censorship of ANC publications, and of those published by its members, slackened in the late 1980s, and was phased out after February 1990. Yet, threatening the publishers and distributors has effectively ensured that copies of the book remain rare and prized items in South Africa. Retail outlets are still unable to obtain copies through the usual channels, and there is evidence to suggest that those who initially imported it directly from Zed have subsequently been coerced into withdrawing it.

Some South African booksellers however, manage to sell it under the counter. The circumstances surrounding the distribution of Mzala's book in South Africa came in the wake of similar issues which surrounded the circulation of another critical biography of the Bantustan leader, published locally. Gerhard Mare and Georgina Hamilton's An appetite for power: Buthelezi's Inkatha and the politics of loyal resistance, had sparked off outbursts of indignation from the ranks of Inkatha and from the Chief Minister himself.

These public indications of Buthelezi's intolerant attitude towards criticism provide a useful background in which to situate the May 1991 attempt to remove the Mzala biography from the shelves of libraries. Many are questioning why Buthelezi had waited so long after the book was published and acquired by libraries, to threaten them. Buthelezi claims that he intended suing Mzala while the latter was alive, that his "lawyers' detectives were actually looking for Mr Nobleman Nxumalo in New York" at the time of Mzala's death; and that "unfortunately... Mzala...is now not here to be answerable to me for what he did in writing his book."

In this regard, it is interesting to recall Mzala's hard-hitting reaction to a review of Chief with a double agenda, in his only known public response to criticism leveled at his work. He identifies himself by giving his full names and his (royal) family connections, and goes on to deal forcefully with the reviewer's criticisms of his book.

Significantly, he states: "The most conspicuous thing since the publication of Chief with a double agenda is the silence. If Chief Buthelezi is slandered why does he not sue in his normal fashion? It is because the book is the truth....The fact that I met Chief Buthelezi and interviewed him in London proves that I was not on a slander campaign, but sought the facts even from the horse's mouth."

Mzala's ability to defend his research and convincingly respond to specific criticisms, provides the context of the following comment made in June 1991 by ANC Southern Natal Region official and academic, Dr. Ian Phillips: "I trust that the fact of Mzala's premature death in February 1991 has not given courage to those who would attack him, knowing that he cannot reply."

By 10 May the latest shameful attempt by Buthelezi to withdraw material critical of him from public debate, was being reported in the Press, which claimed that nine universities had been sent a letter demanding suppression of Chief with a double agenda.

The universities reportedly adopted a cautious tone. The South African law of defamation is interpreted in such a way that circulation of material found to be defamatory after a warning has been given, amounts to publication and is thereby actionable.

Distribution of material found to be defamatory through the medium of libraries could therefore render the latter liable. In the recent past, a University of Natal academic, Dr Michael Sutcliffe had paid Buthelezi 50 000 rand in out of court settlement, following a threatening defamation suit.

Both the University of Cape Town and the University of Natal said they were referring the matter to their lawyers. Professor Colin Webb, Vice president of the University of Natal (Pietermaritzburg), was quoted as saying the Univesirty was not prepared simply to accept the opinion of Buthelezi’s lawyers, but wished to hear other legal views.

Librarians approached by the Press for comment saw Buthelezi’s threat of legal action as a new form of censorship, creating another category of banned work in libraries. This was seen as disturbing, as material banned by the state was now available to all students. The Anti-Censorship Action Group (ACAG), likened Buthelezi through this action to the "... book burning despots of the past. A library", it continued, "is a place where society records its history and its impressions of itself for future generations to judge, and nobody has the right to interfere with that process".

This press coverage was not received with calmness by Buthelezi's lawyers. Replying to a letter from the Deputy University Librarian of the University of Natal (Pietermaritzburg), Jenny Friedman objected to the speed with which the Press got hold of the story, "... without giving us an opportunity to place the matter in its correct perspective", speculating that this was done "... in order to gain an unfair advantage at the expense of Chief Buthelezi". Ludicrously the lawyers chose to interpret Press coverage as an attempt to intimidate their client not to exercise his rights, ironic since one newspaper had described Buthelezi as "...the most litigious public representative in South African history".

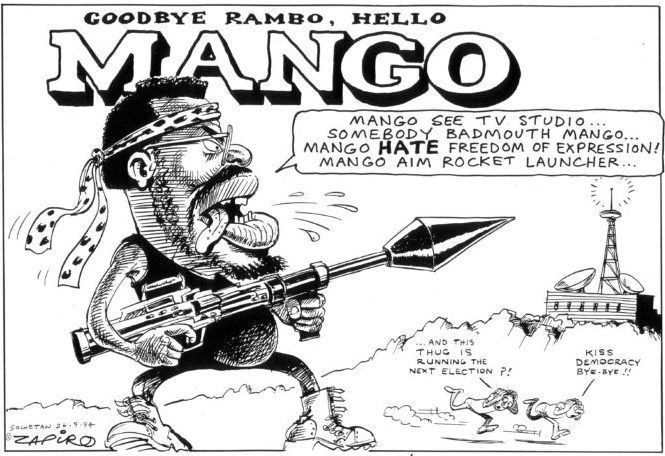

The darling of the mainstream media ( the apartheid media). Buthelezi has been accused, even by the Zulu Royal House, of not missing an opportunity to play for the cameras

Friedman and Friedman took exception to the notion that this action amounted to an attempt at censorship. In this and subsequent letters to the Press, Jenny Friedman argued that Buthelezi was genuinely committed to academic freedom and free to defend himself against "... false, offensive and ugly allegations ...". In doing so, he was only exercising a basic human freedom. To illustrate the point, Shakespeare's Othello (Act 111, Scene 111, Line 155), was quoted:

"...he that filches of me my good name, robs me of that which not enriches him, and makes me poor indeed."

In the same letters, the lawyers indicate they are unfamiliar with the perfectly legitimate literary convention of the pseudonym: "[t]he book ... was written by a man who chose not to reveal his true name or identity".

It is interesting to note that Mzala publicly revealed his identity in April 1989 in the letter to Frontline.

It is not clear whether all university libraries received a letter from Buthelezi's lawyers, but in any case this had become academic by late May when the Committee of University Principals (CUP), having obtained legal opinion, circularized its members advising them to withdraw the book. None of the legal opinions given to universities by their lawyers have been made available for scrutiny, but the general message was that universities, having received lawyer's letters, would be at risk if defamation could be proven, if they continued to circulate the book.

The concept of publication by circulation seemed, however, not to apply to individuals. On 24 May the Registrar of the University of Natal verbally asked the University Librarians to withdraw the book from the shelves. Interestingly, the libraries reported copies of the book missing. When the verbal request to withdraw the book was followed by a letter at the beginning of June, suggesting that the University had taken a final decision to this effect, the matter again became news.

Front page and headline articles in the Saturday News ("University bans Buthelezi book") and Natal Witness ("Varsity withdraws Buthelezi biography"), indicated an angry reaction from academics and librarians. They condemned Buthelezi's action as an attempt at censorship which infringed academic freedom, and viewed the incident "in the context of a long history of attempts on the part of the leadership of Inkatha to block the public dissemination of ideas to which they are antagonistic".

At the time, the book was in use by students studying for a second year Politics course on South Africa, offered on the Durban campus. The matter had been raised by the staff and some librarians with the Joint Academic Staff Association (JASA).

The Registrar, speaking on behalf of the University hastened to point out that the withdrawal of the book was a temporary reaction pending further legal advice. The stand of the University community was implicitly supported by an unusually direct editorial in the Natal Witness which ended with the opinion that, "[t]he unequivocal determination of the universities to maintain their academic freedom is one of the most stalwart bastions that democracy has".

Friedman and Friedman responded to this latest Press coverage letters to the editors of the Daily News and Natal Witness protesting Buthelezi's right to defend himself against public attack. Jenny Friedman requested that her argument be given equally prominent coverage, and that the matter be put "...in its correct perspective”, but used the same well-worn points about a commitment to academic freedom and the nature of defamation, made in her earlier letter to individuals.

A more polemical approach was used by the Inkatha owned newspaper Ilanga, under the heading "Propagandists at work”. This was a straight-forward attack on the ANC and its supporters within the University of Natal, which it accused of using the allegedly defamatory material in Mzala's book as a vehicle for political gain.

It named Ian Phillips and Michael Sutcliffe as ANC "apparatchiks" and "commissars" and described academics in the University as the "...ANC's fetch and carry boys...". The language and line of argument in this article can be seen in terms of a tradition of hostility on the part of sectors of Inkatha toward the University of Natal, embodied in the confidential report compiled by the Inkatha Institute in April 1989 concerning political activity on the campus and its implications for Inkatha and the KwaZulu government.

The Black Students' Society on the Durban campus of the University of Natal reacted angrily, and urged the University's Administration to stand up to the repression of intellectual growth, as it had done in the past, and this time, to take the struggle for academic freedom into the courtroom. A notice board in the foyer of the E.G. Malherbe Library, displaying press clippings on the issue, was avidly read by library patrons; as was a similar display mounted in the Pietermaritzburg campus library in August.

Requests for Chief with a double agenda soared. On 26 June 1991, Professor of History at the University of Natal (Durban), Paul Maylam, responded to Jenny Friedman in the letters page of the Daily News. Maylam challenged the lawyers' arguments on the basis that they merely "claim" the book is libelous, and level no specific criticism with regard to the book's contents; their "accusations are vague and general". Rather than suppressing the opinions of his opponents, Buthelezi should engage with them in open debate:

"If a democratic culture is to be developed in South Africa it is crucial that these matters be debated rather than suppressed."

The letters page of the Weekly Mail also reflected public interest in the debate. One writer defended his/her right to criticise public figures, and criticised the University for withholding the book, suggesting that perhaps the University had been intimidated into doing so. Buthelezi was accused of exhibiting the first signs of totalitarianism. Interestingly, other letters published around the same time questioned Inkatha's stand on press freedom, and Buthelezi's links with the CIA.

On 15 July, it was reported in the press that the University of Natal had released a statement stating that the book had been returned to the shelves of the University libraries, following legal advice:

"In the university's view it has always been a matter of public policy that books, even if critical of public figures should be available for critical study by the scholarly community".

Jenny Friedman, on being approached for comment, indicated that she had not been officially notified by the University of its decision, but that she would like to reiterate that making the book available constituted "committing a civil wrong" as the book was defamatory. It is understood that the University intended officially notifying Friedman and Friedman of the decision.

Subsequent to the University's decision, it was ascertained that the Durban Municipal Library and its reference collection, the Don Africana Library, had also received letters from Friedman and Friedman requesting that the Mzala book be withdrawn. The City Librarian indicated that the lawyers of the Durban Corporation had advised her to comply.

At their Annual General Meeting on 27 July, the Library and Information Workers' Organisation passed a resolution welcoming the return of Chief with a double agenda to library shelves, and urging other libraries intimidated into removing it to follow suit. The resolution also called for support for library and information workers faced with attempts at censorship, both formal and informal, from lawyers, educational and local government authorises, cultural organisations, the press, and universities.

In discussing controversy surrounding Chief with a double agenda agenda, it is useful to investigate the book's reception in academic and public circles. Reviews in academic journals, as well as those written by serious political analysts, leave one in no doubt that this is a study worthy of distribution and careful scrutiny.

On the one hand, it is placed next to Gerhard Mare Hamilton's An appetite for power: Buthelezi’s Inkatha and the politics of loyal resistance as one of the two crucial texts which are critical of Buthelezi and Inkatha, and in opposition to the authorized and sycophantic biographies. Together, these works are presented to students of modern South Africa as constituting the essence of the debate around Buthelezi.

On the other hand, Mzala's book is given special attention by virtue of the author's position in the ANC, and his access to documentation which has been unavailable to local writers. It is described more than once in this context, as authoritative.

"The author's association with the External Mission of the ANC...gives unusual authority to his account of the ANC's attitude towards Buthelezi and allows him to provide genuinely new material on the relationship between them. In this respect, Mzala's 'insider' status does not detract from the book, but is its most appealing quality....The author's partisanship has not resulted in a loss of objectivity and balance, for it is written with a fairness that would certainly have been absent had the roles been reversed".

In addition, Nicholas Cope asserts in his joint review of the Mzala text and the Mare and Hamilton work that, "it is partly because the books are partisan that they make such informative texts regarding the political conflicts and alliances particular to Natal, and the broader political issues that are at stake".

In none of the reviews under consideration, is Mzala accused of leveling unsubstantiated rhetorical accusations at a political opponent of the organisation to which he is allied. Rather, he reaches his final conclusion 'Via substantial argument, both empirical and interpretative"; in addition, "Mzala is...a considerable scholar. This is no ephemeral polemical treatise. It is, in the main, a reasoned, informative, well-researched and tightly argued attack on a political opponent. Even the targets of such works will concede this is a genre with valuable historical antecedents".

Even Nomavenda Mathiane, in a review for Frontline magazine which accuses Mzala of using "sordid statements" to criticize Buthelezi, concedes that "the book is a work of an academic and historian" and that it is "a well researched document", giving "a spellbinding analysis of black history up to the present day".

Documents accessed by author James Sanders for his book Apartheid’s Friends (2006) revealed the extent to which Buthelezi worked directly with the apartheid state from 1985 to fuel the civil war

Reviewers concentrate on some of the central themes of the book:

- Buthelezi's presentation of himself as an opponent of apartheid whilst being in the paradoxical position of having been granted his political position in terms of the Bantustan system;

- Buthelezi's claim that his position in the Zulu state is justified in terms of his family's traditional relationship with the Zulu Kings, something disputed by Mzala with fairly convincing evidence;

- Buthelezi's calls for peace among rival groups of South Africans, contrasted with war talk directed at the ANC from KwaZulu or Inkatha platforms; Buthelezi's claim to a position in the ranks of the national liberation forces, given his virulent opposition to the ANC and allied organisations, including trade unions.

The key paradoxes of Buthelezi's position in South African politics are considered by reviewers to have been adequately and competently presented by Mzala, although he is criticised for not having dealt with the "political magic" of Inkatha, the successful mobilisation of its followers, the essence of the organisation at work in the mid-1980s, and of course, how the ANC is going to approach the problems Inkatha presents.

The conclusion of all reviews under consideration here is that Mzala's biography of Buthelezi constitutes an important and indeed indispensable contribution to the contemporary South African political debate.

The book was received "warmly" when it was published in early 1988, and those with a general interest in South African politics - and specifically those "with' delusions concerning Inkatha’s democratic credentials" - were invited to read the book "diligently". A review journal published specifically for librarians in American college and university libraries recommends the book for "general readers, upper-division undergraduates, and graduate students".

The opinion of academic and popular reviewers underlines the extent to which Buthelezi's actions pose a dangerous threat to the academic freedom of universities, for the following reasons:

- The book was withdrawn from library shelves solely as a result of the opinion of certain lawyers. At no stage has a Judicial process deemed the book to contain defamatory matter. This situation - threatened action, and the universities failing to challenge it - could be used to effect the indefinite withdrawal of information from public debate. This amounts to an act of censorship, even if not intended.

- Not only was the book suppressed, the reasons for complaint have not been made public. Is it one word, a sentence, a paragraph, a page, or a chapter that is causing offence? And if it is causing offence, is it untrue? Even if it is untrue, is it not in the public interest that it be made known? In the meantime the rest of the book is forbidden. Need the universities be reminded that the circulation of information (and related belief and opinion) and the presentation of contradictory evidence (and criticism and opinion), debating truths and untruths, represent the very basis of the progression of academic activity. The complainant should be obliged to furnish reasons for dissatisfaction, and engage in the debate, rather than shelter behind vague statements and objections.

- Withdrawal of books like this one threatens the academic process. It emphasizes the fact that any politician or public figure who objects to what is written about him/her can use the law of defamation to close down debate. The only way universities can challenge this is to let the law take its course. As pointed out by Professor Maylam, the genre of biography is put at risk in this way. In the case of Chief Buthelezi, "[a]s a political leader it is his responsibility to defend that position, not to suppress the arguments of his opponents"

By allowing these issues to be aired in court, the universities can attempt to protect a freedom central to their existence. They owe it to society as a whole to protect extremely fragile freedoms such as that to circulate ideas and information.

But, there is more at stake here than a concept with relevance to freedom in academic debate. The right to information about public figures and their activities is one to which South Africa has only recently been introduced. A judge in a recent defamation case ruled that although a newspaper report contained highly critical material about an individual which was not entirely true, because of the issue and the people involved, it was in the public interest to allow its unhindered publication.

For far too long South Africans have been denied information about the ways in which those who command the economic and political heights of the State exercise their power, and for what ends.

The development of a participative democracy in South Africa as a step towards the establishment of greater justice for all its people, is dependent upon a full and free flow of information. The Neethling case has already shown an encouraging recognition by the judiciary that those who are employed by the State, or seek to wield power within it, must be prepared to have their actions exposed to public scrutiny; and that those, such as journalists, who facilitate this process must be offered reasonable guarantees against legal retribution as long as they are acting in the public interest.

Chief Buthelezi has chosen voluntarily to be a public figure and a politician; the public has a right to know as much as possible about him and his activities. Recent exposes about secret alliances between Inkatha and the forces of apartheid, suggest that there is perhaps even more to the Buthelezi saga than critics and opponents like Mzala, Mare and Hamilton have indicated.

It is ironic that only a few weeks after receipt of the lawyer's letter demanding withdrawal of the book, the funding scandal surrounding Inkatha, UWUSA and other right wing organisations surfaced, emphasizing the point that we need to have access to as much information as possible about public figures, especially those with a propensity to sue anyone who writes critically about them.

Indeed, in view of the events which have taken place since the 1988 publication of Chief with a double agenda, the information Mzala presents becomes increasingly worthy of scrutiny.

In mid-1991, Buthelezi's involvement with conservative and militaristic international figures and organisations, and controversies surrounding Inkatha locally have prompted academics, analysts, journalists and activists to turn to critical research in an attempt to define the nature of the mobilisation evident in the ranks of Inkatha, the role of violence and intimidation in current political interaction, Buthelezi's personal political ambition, his interplay with the State in the negotiation processes, and the ultimate cost of ignoring, misrepresenting or underestimating the entire Buthelezi-Inkatha phenomenon.

Even more recently, covert links between Inkatha and the South African Police, and other government departments and officials, have been exposed. These links were allegedly orchestrated with the objective of undermining support for the ANC and disrupting its ability to re-establish itself inside South Africa after the unbanning in February 1990.

The exact nature of these links and of the relationship between Buthelezi and Inkatha, and the State, is not as yet established, and the public awaits further evidence. Activists within the liberation movement who have been exposed to anti-democratic, violent and coercive activity on the part of Inkatha supporters, have long suspected the existence of an alliance and need no convincing. For them, the appearance of academic and critical texts, like Chief with a double agenda, serve to contextualise their daily struggles against reactionary forces which seem to be in collusion with the police, army and other agents of the state.

It is in this regard that the contribution of Mzala's work to the future of South Africa must be seen. It may well be the case that the information presented by Mzala, and by Mare and Hamilton in their book, together with the information exposed recently by the Press, may contribute to the disarming of a potentially destructive and disastrous factor in the negotiated settlement of South Africa's future.

Censorship in South Africa has always been a flexible institution adapting to and with the political needs of the time. At present there is a distinct trend away from methods based on statute towards informal censorship derivative of violence and intimidation. Another back door method, given the evidence presented above, might well be the law of defamation. The use of defamation law in a case such as that outlined above, amounts to an act of censorship, even if this is not intended by the complainant.

The universities, with their stated commitment to academic freedom and to uninhibited and equal exchange of opinion and information, have a responsibility to society to resist attempts to curtail these freedoms. It is ironic that just one year after the University of Natal took a decision to defy the Publications Act , it is faced with a different and equally dangerous threat to academic activity.

Given this situation, there seems to be a strong argument for reform of the law of defamation. Quite clearly the public interest factor needs to be well entrenched, but there is good reason to argue for mechanisms which enhance rather than suppress discourse.

At the moment, writers on public figures and sensitive issues are justifiably nervous about the large sums for which they might be liable should a court decide that their material is defamatory. In some countries, provision has been made for more imaginative remedies than suing for damages. In France, the droit de reponse dates back to the nineteenth century and gives anyone mentioned in a newspaper, even in a non-defamatory way, a right of reply.

The law of defamation in Germany, the United States and various South American countries has followed the French example to variable degrees. It is interesting to note that the ANC's Bill of Rights mentions the right of reply in connection with its clause on freedom of thought, speech, expression and opinion, and a free press. All societies need laws to guard against defamation so as to balance freedom of expression and the right to secure individual reputations.

The incident documented in this article indicates that the battle for freedom of information and opinion, now as in the past, must be carried forward in as many different fronts as possible.

There are important moral and pragmatic reasons why South African universities should promote public interest cases such as this one. This presents a crucial opportunity for universities to implement their stated commitment to these freedoms - which are, after all, basic human rights.