The definition of a Banana Republic: A blow by blow account of how a corrupt justice system brews a civil war in South Africa

By Adv Paul Ngobeni

There is nothing lawful or historic about Parliament’s vote on the removal of the Public Protector that was scheduled for Tuesday March 15 2021. More broadly, the vote was about exposing judicial incompetence and corruption, laying bare the sheer incompetence of the ruling party the ANC, a party enmeshed in factional squabbles and being misled by the racist Democratic Alliance…

This vote was not about the alleged incompetence of a black woman, the Public Protector – it was about what I call Zuma exceptionalism and the political vendetta of Ramaphosa and Gordhan who have blatantly manipulated clear legal statutes and code of ethics to cover up their own misconduct as shown through evidence below.

Are there facts to substantiate these damning allegations of “judicial incompetence and corruption” in the first place? Answer is absolutely yes.

For starters, the High Courts through three separate judgments have pronounced that the Public Protector incompetently relied on a “wrong” version of the Code of Ethics and the Independent Panel led by retired Concourt Justice Nkabinde also claims that the Public Protector relied on a “wrong code” and is deserving of removal for incompetence.

Mkhwebane’s alleged sin is that she used a 2007 version of the Code of Ethics for members of the executive, the same code used by her predecessor and the Constitutional Court itself. Most puzzling, Justice Bess Nkabinde was on the Constitutional Court panel that decided the “Nkandla” case, Economic Freedom Fighters v Speaker of the National Assembly and Others; Democratic Alliance v Speaker of the National Assembly and Others[2016]ZACC 11.

There the Concourt stated that previous Public Protector Madonsela “concluded that the President violated the provisions of the Executive Members’ Ethics Act 7 and the Executive Ethics Code 8. These are the national legislation and the code of ethics contemplated in section 96(1).” Specifically, the Concourt cited “ Chapter 1 of the Ministerial Handbook: A Handbook for Members of the Executive and Presiding officers(7February 2007) at pages 7-15.

Say what? Indeed the Concourt used and relied on the same Code the “incompetent” Mkhwebane used. Justice Nkabinde knew this as she participated in issuing the historic Nkandla judgment.

Quite logically and in keeping with legal principles, the Concourt did not rely on the earlier superseded version of the Executive Ethics Code which was promulgated by Presidential Proclamation R41 of 2000 in terms of Section 2(1) of the Executive Members Ethics Act.

Paragraph 2.3(a) of the earlier Code reads as follows: “Members of the Executive may not wilfully mislead the legislature to which they are accountable.” The differences in the 2000 and the 2007 Code of Ethics are quite substantial and very important - the earlier 2000 version stated only that “Members of the Executive may not wilfully mislead the legislature to which they are accountable.” But the 2007 version added the words “may not willfully or inadvertently mislead.”

In short, Public Protector Advocate Mkhwebane correctly relied on the 2007 version which was also used by her predecessor Madonsela which had received judicial imprimatur (formal and explicit approval) from the apex court in the Nkandla judgment. How can Justice Nkabinde who participated in the Nkandla judgment and used the 2007 version author a report that says that the Public Protector was ‘incompetent” because she relied on the same version of the Code that the Concourt used in the Nkandla judgment?

If the 2007 version is the “wrong” code does that render the entire Nkandla judgment null and void? Why would a judge so easily change her position and contradict her own judgment to advance the politically motivated agenda of constant ad hominem (Appealing to personal considerations, rather than to fact or reason) attacks on a Public Protector who used the same law that the Concourt used in Nkandla?

Did Ramaphosa and Gordhan have any role in this perversion of the law and undermining of Chapter 9 institutions in such a flagrant and scandalous manner? Absolutely yes!

When Ramaphosa was a Deputy President and Gordhan served in the Zuma Cabinet, they both accepted that the applicable code was the 2007 version which was used by Madonsela and later Mkhwebane. All that changed when both Ramaphosa and Gordhan were found guilty of misleading parliament – they changed tack and argued that the favourable but superseded 2000 version of the Code must apply to their conduct and not the later 2007 version relied upon by the Concourt.

This was wicked clever because the 2000 version only proscribes Members of the Executive “willfully” misleading “ the legislature to which they are accountable.” But the 2007 version added the words “may not willfully or inadvertently mislead.”

Under the latter version both Ramaphosa and Gordhan are guilty even if they acted “inadvertently” when they misled Parliament. It is for that reason that they resorted to using an outdated law to shore up their phony defense and the obsequious (attempting to win favour from influential people by flattery) judiciary simply obliged. If I am wrong and Ramaphosa and Gordhan are correct that the 2000 version is the applicable law, then the entire Nkandla judgment rest on a false legal premise and is null and void. Are we now dealing with Zuma exceptionalism? They cannot eat their cake and have it at the same time.

Clearly the judiciary appears to have taken the position that these provisions of the 2007 Code were only applicable to President Zuma. When Ramaphosa was being investigated for lying to Parliament about the Bosasa payments to his son, he gave a false answer but admitted that he misled Parliament inadvertently.

Likewise, when Pravin Gordan was investigated for lying about attending meeting where a member of the Gupta family was present, he claimed that he was not guilty because he did not “deliberately mislead” Parliament. Incredibly, the High Court judges came to both Ramaphosa and Gordhan’s rescue by relying on an old 2000 version of the Code which only prohibited “deliberately” misleading. Such damnable manipulation of legal rules and processes deserve a commission of enquiry.

This was simply unprecedented in world jurisprudence in that the judges knew that the Executive Ethics Code contemplated by the Executive Members’ Ethics Act was published by the President on 28 July 2000 and amended on 7 February 2007 by the same President (Mbeki).

Further the previous Public Protector Madonsela used the 2007 version of the Code in writing several adverse reports against Ministers such as Shiceka (https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/shicekareport0.pdf ) and Premiers (Yes We Made Mistakes: Report of an investigation into the alleged improper procurement of communication services by the Department of the Premier of the Western Cape Provincial Government Report No1 2012/2013 http://uscdn.creamermedia.co.za/assets/articles/attachments/40634_draft_final_report_version_3.pdf ) at least since 2010.

The Constitutional court’s endorsement of and reliance on the 2007 Executive Ethics Code is binding on all lower courts and it is unfathomable that a High Court judge would resort to using the old 2000 version of the Code in clear defiance of the binding precedent of the apex court.

It is trite that decisions of the Constitutional Court are binding on all lesser courts based on the principle of stare decisis, which is a juridical command to the courts to respect decision already made in a given area of the law. This means that the High Court must follow the decisions of the courts superior to it even if such decisions are clearly wrong. The statement of principle by Didcott J in Credex Finance (Pty) Ltd v Kuhn 1977 (3) SA 482 (N) that is thus concisely summarised in the headnote to that judgment is in point:

"The doctrine of judicial precedent would be subverted if judicial officers, of their own accord or at the instance of litigants, were to refuse to follow decisions binding on them in the hope that appellate tribunals with the power to do so might be persuaded to reverse the decisions and thus to vindicate them ex post facto. Such a course cannot be tolerated."

In practical terms this means that once the Constitutional Court ruled the 2007 Code of ethics was valid and applicable it was no longer open to the High Court to prefer the earlier 2000 version of the Code which had been superseded. The Constitutional Court, in Camps Bay Ratepayers’ and Residents’ Association & another v Harrison & another 2011 (4) SA 42 (CC), paras 28-30, expressed itself in no uncertain terms about observance by courts of the maxim stare decisis or the doctrine of precedent. Brand AJ, in delivering the unanimous judgment of the court said:"Considerations underlying the doctrine were formulated extensively by Hahlo & Kahn [Hahlo & Kahn The South African Legal System and its Background (Juta), Cape Town 1968) at 214-15]. What it boils down to, according to the authors, is: '(C)ertainty, predictability, reliability, equality, uniformity, convenience: these are the principal advantages to be gained by a legal system from the principle of stare decisis ([law]) the principle of following judicial precedent).'

Observance of the doctrine has been insisted upon, both by this court and by the Supreme Court of Appeal. And I believe rightly so. The doctrine of precedent not only binds lower courts, but also binds courts of final jurisdiction to their own decisions. These courts can depart from a previous decision of their own only when satisfied that that decision is clearly wrong. Stare decisis is therefore not simply a matter of respect for courts of higher authority. It is a manifestation of the rule of law itself, which in turn is a founding value of our Constitution. To deviate from this rule is to invite legal chaos." (Footnotes are omitted.)

The current Public Protector correctly relied on the 2007 version which was used by her predecessor and had received judicial imprimatur from the apex court.

We have all watched in horror as the various High Courts engaged in the constitutionally impermissible spectacle of prefering a version of the Code which is favorable to Ramaphosa and Gordhan while ignoring the later version which was used against Zuma in the Nkandla judgment.

In the Rogue Unit judgment, the High Court ruled that “the Public Protector’s reading and interpretation of paragraph 2.3(a) of the Executive Ethics Code is wrong in law: The Code prohibits members of the Executive from “wilfully” misleading the legislature. The wording of the Code is clear and does not contain a provision that an “innocent” mistake constitutes a contravention of the Executive Ethics Code.” This deliberate disregard of the Concourt’s “Nkandla judgment” and egregious misreading of the law to favour certain political adversaries is sufficient to make anyone think twice about entrusting their fate in the hands of our judiciary. Only heartless corruption can account for this egregious misreading of clear statutes.

In its recent scathing judgment against the Public Protector in the “Rogue Unit” case, the High Court (Baqwa J) embarrassed itself and highlighted its own confusion by concluding that:To claim that Potterill J “deliberately omitted the words ‘inadvertently mislead’” from the actual Code, is simply astonishing. Besides being a Public Protector, Adv Mkhwebane is officer of this court owes it a duty to treat the Court with the necessary decorum.

She not only committed an error of law regarding the Code but was also contemptuous of the Court and Judge Potteril personally. What makes this reprehensible conduct worse is that the remarks by Adv Mkhwebane were made under oath, when she ought to have known about the falsity thereof. This clearly held the possibility of misleading this court. This is conduct unbecoming of an advocate and officer of this court. She owes Judge Potteril an apology. The Registrar of this Division is requested to send a copy of this judgment to the Legal Practice Council for consideration.

What is truly astonishing is not the Public Protector’s alleged error but the flagrant error made by the three judges who claim the Public Protector “not only committed an error of law regarding the Code but was also contemptuous of the Court and Judge Potteril personally.”

Since when has it been contemptuous to point out that a court has resorted to using an old superseded version of a statute to justify a ruling in favour of a litigant? What right-thinking judiciary would order a Public Protector who is virtually the custodian of the Code of Ethics to apologize for being correct and for insisting that the Constitutional Court precedent be scrupulously followed? What honest and conscientious judiciary would embarrass itself by sending a copy of a totally incompetent judgment to the Legal Practice council with the recommendation that the latter act on it to the detriment of an advocate who happens to be correct on the facts and the law? The High Court’s misapprehension is further made clear when it states:

62. In the matter of The President of the Republic of South Africa v The Public Protector (The Information Regulator Amicus Curiae) 12 the full bench of this division similarly criticized the Public Protector’s flawed understanding of the contents of section 2.3(a) of the Executive Ethics Code:

"[207] Of similar concern is her confusion over the proper version of the Executive Code. She has not explained how she committed this error. Her conduct in this regard goes further than simply having reference to two different versions of that Code. The legal test for a violation of the Code by misleading the National Assembly was fundamentally different in the two versions. Instead of appreciating the difference between the "willful" misleading of the National Assembly, and the "inadvertent" misleading of it, she asserted that if she had made an error at all it was an immaterial error of form over substance. This submission shows a flawed conceptual grasp of the issues with which she was dealing. [208] Like any official required to make pronouncements to the public, the Public Protector must surely strive to be as clear as possible in her findings. Her reasoning on the disclosure issue was muddled and difficult to understand. It failed to explain to the public why she had found that the President of the country had wilfully breached the duty of transparency established by the Code. Indeed, her conclusion inexplicably found that at the same time the President had also inadvertently misled Parliament, sowing further confusion."

The claim that the Public Protector has “confusion over the proper version of the Executive Code” is simply unfounded. The High Court after acknowledging that there were two different versions of that Code simply ignored the latter 2007 version and attacked the Public Protector and her ruling while elevating the 2000 version which favoured Gordhan and Ramaphosa.

This erroneous ruling makes clear that those judges attacking the Public Protector daily and hammering her for alleged incompetence are actually the main culprits guilty of gross judicial incompetence. The dramatic unsavory language and epithets they frequently use against her in the judgments is used to provoke public condemnation against her and to obfuscate the fact that the judges have been drafted as willing foot soldiers in the titanic battle between Ramaphosa’s forces and those perceived to be sympathetic to President Zuma.

It is constitutionally impermissible and scandalous for a retired Concourt judge Nkabinde to ignore the very Nkandla judgment she participated in and to pronounce that a Public Protector who relied on that very precedent is “incompetent” and must be removed. It is significant that in the recent Concourt judgment regarding the Gordhan interdict the Court remarked that:

[97] This matter has garnered much public interest and criticism. It is a matter which has a political bite to it. It is thus understandable why the public would have an interest in it. However, it must at all times be remembered that courts must show fidelity to the text, values and aspirations of the Constitution. A court should not be moved to ignore the law and the Constitution, and merely make a decision that would please the public. The rule of law, as entrenched in the Constitution, enjoins the judiciary, as well as everyone within the Republic, to function and operate within the bounds of the law. This means that a court cannot make a decision that is out of step with the Constitution and the law of the Republic. It must impartially apply the law to the prevailing set of facts, without fear, favour or prejudice. (emphasis added).

The claim that the Public Protector has confusion over the proper version of the Executive Code is simply unfounded. The High Courts, after acknowledging that there were two different versions of that Code, simply ignored the latter 2007 version and attacked the Public Protector for not using the earlier version favouring Ramaphosa and Gordhan.

This erroneous ruling makes clear why the stakes are very high and the matter has been appealed to vindicate the public Protector and to show the judicial incompetence that she is facing daily. I find it curious that Madonsela who hates her successor so much has conveniently not come to her defense even though she repeatedly used the 2007 version of the Code herself.

Likewise former President Mbeki promulgated the 2007 Code and some ministers who served in his Cabinet and were governed by the Code are still serving in the Ramaphosa cabinet. Why are all these illustrious ministers and people quiet? Are they hypocritically going to allow and participate in a nonsensical parliamentary “vote” on removal of a Public Protector based on concocted charges and daylight perversion of legal principles? Does that advance the fight against corruption one iota?

Parliament’s Own Resort to Zuma Exceptionalism and Violation of the Sub Judice Rule in the Public Protector Matter.

Unfortunately, the alarming incompetence discussed above is not confined only to the judicial or executive branches. Parliament is flagrantly embarking on a violation of Rule 89 of the Rules of Parliament and has thrown the sub judice principle overboard.

The sub judice rule means that the merits of a case that is still being considered by a judge or court, should not be discussed by MPs and government officials. To emphasise the high constitutional nature of the rule it suffices to state that it stands as an expression of the relationship between the different branches of government—the legislative branch and the judicial branch.

Parliament determines what the law should be, but it is for the courts to determine in each particular case how the law is to be applied. In criminal matters, it is not for Parliament to decide guilt or innocence. In civil cases pending trial or appeal Parliament does not adjudicate such case. That is a matter for a court of law.

Where the rule is engaged, Parliament does not embark, either by debate or by question, on an examination of matters that are for adjudication by a court. Not only is this prejudicial and unfair to those involved in judicial proceedings; it is contrary to our constitutional practices. If Thandi Modise, the Speaker was not a partisan CR 17 factionalist baying for Advocate Mkhwebane’s blood she would have been vigilant to ensure that the sub judice rule is maintained sacrosanct.

National Assembly Rule 89 governing “Matters sub judice” is absolutely clear and states unequivocally that: “No member may reflect upon the merits of any matter on which a judicial decision in a court of law is pending.”

In South Africa, all branches of government are subject to scrutiny by the courts. Even the President is subject to the provisions of the Constitution. see President of the Republic of South Africa & Anor v Hugo 1997 (4) SA 1 (CC) at paras 12 and 28, as well as Executive Council, Western Cape Legislature & Ors v President of the Republic of South Africa & Ors 1995 (4) SA 877 (CC). The learned Judge President Hlope, in the case of De Lille & Anor v. Speaker of the National Assembly & Ors 1995 (4) SA 877 (CC) ruled:

“The National Assembly is subject to the supremacy of the Constitution. It is an organ of state and therefore it is bound by the Bill of Rights. All its decisions and acts are subject to the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. Parliament can no longer claim supreme power subject to limitations imposed by the Constitution. It has only those powers vested in it by the Constitution expressly or by necessary implication or by other statutes, which are not in conflict with the Constitution. It follows, therefore, that Parliament may not confer on itself or on any of its constituent parts, including the National Assembly, any powers not conferred on them by the Constitution expressly or by necessary implication.”

This was an expression of the simple truth that in a constitutional democracy, the authority to interpret the law as well as Parliament’s rules vests in the judiciary.

Thus, the sub judice rule applies by virtue of the operation of the law once a matter is before the courts. Parliament’s violation of the sub judice rule is a disregard for the Judiciary, the only arm of the state vested with constitutional supremacy in interpreting the law in terms of the constitution. Such violation is likely to prejudice the justice delivery process. A defining interpretation of the sub judice rule was made by a neighboring country judge, Justice Bere in the Zimbabwean case of Austin Zvoma v. Lovemore Moyo & Ors, HC1249; https://zimlii.org/zw/judgment/harare-high-court/2012/23/.

The learned judge observed that Standing Order 62(d) of the House of Assembly is clear in that when a matter is pending before the Courts, ‘…House members are obliged to respect the Court process until a determination has been made’. The learned Judge stressed that despite the fact that the Speaker and other respondents had been duly served with the case number, debate on the motion continued in complete defiance or violation of the Standing Order in question. Such disregard by the House of Assembly of its own rules resulted in the nullification of the motion that it had adopted.

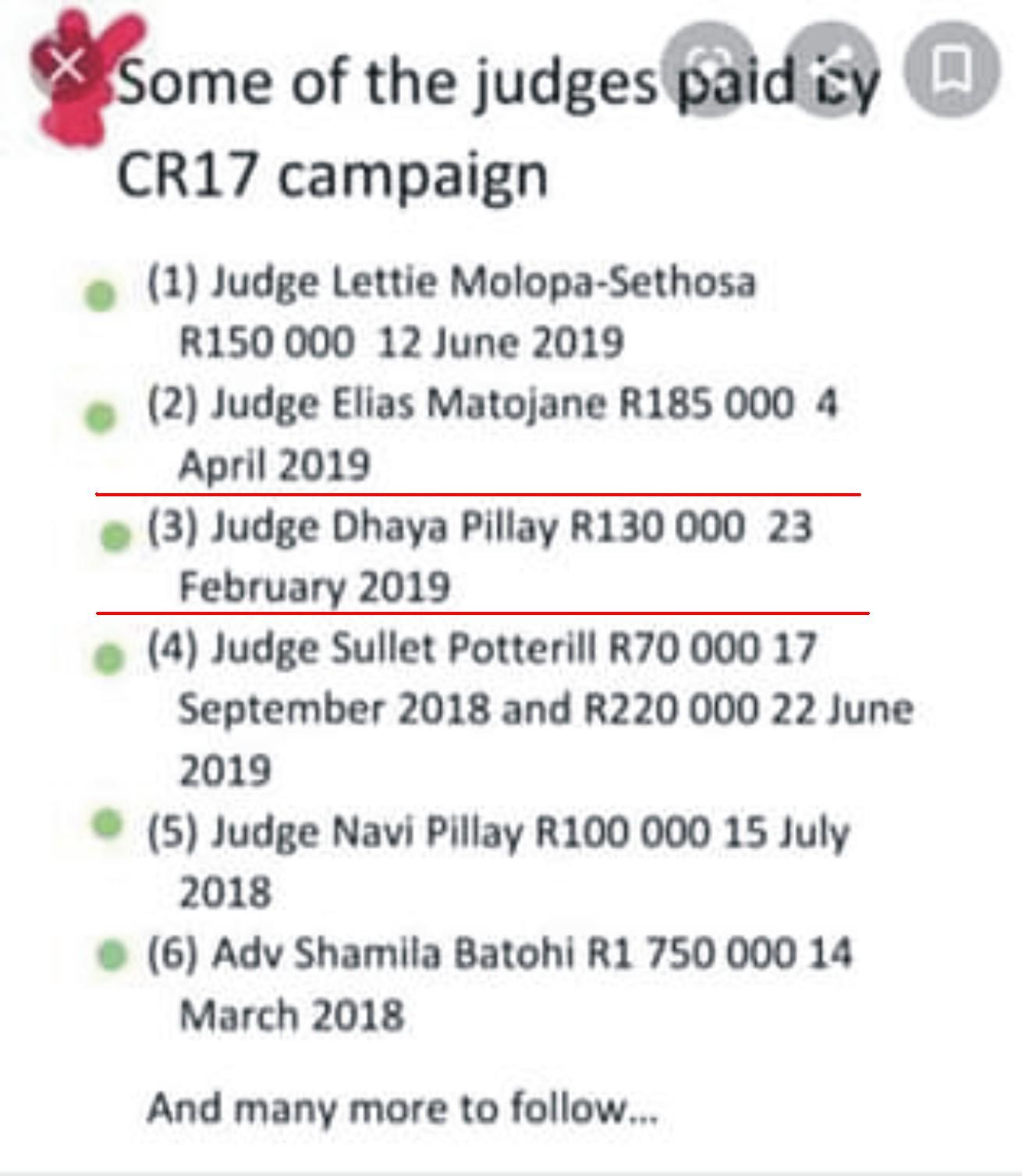

The nullification effectively quashed the interpretation of the sub judice rule the Speaker had made on 5 December 2011. Justice Bere expressed the strong view that courts would not want to assist ‘the House in assaulting its own rules…’ I venture a prediction that the Public Protector may actually have the final laugh in these fake impeachment proceedings – Parliament’s flagrant disregard of its own rules will result in the nullification of any Public Protector removal motion that it adopts. Not all judges in our judiciary can be bought with money!

Voting By MPs with Conflict of Interest

It is noteworthy that the majority of the complaints involving politicians investigated by the Public Protector are initiated by political parties or their members. When the same parties or their representatives in the National Assembly who are in litigation with the Public Protector (or have cases pending before her) are allowed to initiate removal proceedings a specter of a serious conflict of interest looms large.

The pivotal question is whether any of the Ministers or MPs who are currently under investigation by the Public Protector or have had adverse findings made against them must be allowed to participate in a committee set up by Parliament to decide the Public Protector impeachment?

Some like Mbalula have smoldering grievances against the Public Protector because she exposed their corruption and they have a clear conflict of interest. In this regard, President Ramaphosa against whom the Public Protector has made adverse findings and who is currently involved in ongoing litigation against the Public Protector is a text-book case of a conflicted official who is likely to play a role in the removal process envisaged for the Public Protector. Has the Chief Whip Majodina even made minimal efforts to ensure that MPs with a conflict of interest are not allowed to use their votes to retaliate against the Public Protector?

Legal eagle Adv Paul Ngobeni says Fikile 'Mrekza' Mbalula had an obvious sinister motive to vote against Mkhwebane

Political parties are the main complainants before the Public Protector and some have been vociferous in condemning her for issuing reports and remedial orders which did not suit their political agendas. Some parties like the DA are currently involved in litigation against the Public Protector – should they be allowed to invoke the Section 194 removal enquiry to deal with matters in which they were losing litigants or matters still pending judicial decision?

Both Speaker Modise and ANC Chief Whip Majodina are deafeningly silent in this regard and that speaks volumes for ANC as a ruling party in charge of a capable developmental state!