Jacques R Pauwels: “If peace ever descends on earth, it would be a catastrophe for America’s big business”

By Jacques R. Pauwels

This is foreword from the book: Big Business and Hitler...

Let us now examine the relationship of the corporations and banks of Germany and the United States, in particular, and of big business in general, with Hitler. Which involved supporting him from the beginning of his political career and/or helping him to come to power in Germany, profiting from his regressive social policy and rearmament program. Assisting him as he unleashed and waged his war of conquest and rapine and organized the Holocaust, earning unprecedented profits in the process. And ultimately managing to survive the demise of Nazism and fascism in general while preserving their wealth, power and privileges…

“Business” is an ambiguous term. On the one hand, it refers to an activity,

doing business, and “big business” means doing business on a large scale,being involved in important economic activities generating major profits. On the other hand, the term “business” can also be used to refer to the kind of people who engage in such activities. And in this case “big business”designates people who are involved in important, large-scale money-making projects, in other words, industrialists and bankers.

The term “capitalists” is also appropriate, because these are the owners and managers of capital. In fact, the terms “capital” and “big business” are virtually synonymous. (The German language, incidentally, features the term Großkapital, “big capital.”). The term “capital” does not merely refer to money, not even to “big money,” but to the means of production, that is, the institutions, real estate, technologies, machinery and other factors, which, when combined with raw materials and the labour provided by workers and other wage earners, generate goods and services and produce wealth.

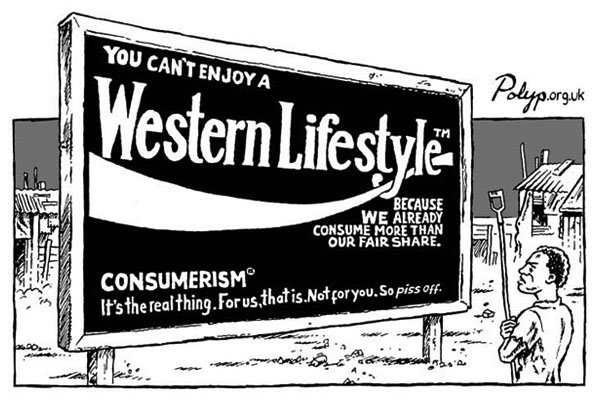

Wealth is thus the output of a process in which capital as well as labour and raw materials constitute the three forms of input. This production process is not an individual but a collective effort, in other words, a social process; and the wealth generated in this fashion may be described as a “social product.” However, in a capitalist system, the lion’s share of this social product is appropriated by the owners of capital, namely in the form of profits, while those who supply their labour receive only a relatively minor part of the social product, represented by their wage or salary.

In the contemporary “Western world,” the industrialists and bankers belong to the upper class, to the social “elite” or “establishment.” In Europe, they mingle easily with the folks who used to monopolize the apex of the social pyramid, namely, the members of the nobility (or aristocracy), whose power and wealth were based on large land ownership, on landed property.

In Europe, the upper class is still composed not only of the tycoons of industry and finance, who sometimes also control considerable landed property, but also of a comparatively restricted number of aristocrats, including the monarchs of countries such as Britain and the Netherlands. These aristocrats not only own vast tracts of landed property but also possess fat portfolios of shares of corporations and banks, so that they can also be considered to belong to the world of industry and finance.

The British royal family, for example, not only owns enormous land holdings for which it collects rent but is also one of the major shareholders of corporations such as Shell. Representatives of the world of industry and finance as well as Europe’s nobility occasionally meet in “exclusive” locales such as Davos, in Switzerland, or Bilderberg, in the Netherlands, to discuss issues of common interest. It would be wrong to say that they are there to organize “conspiracies.” But they certainly use the opportunity to draw up plans and strategies, and to become acquainted with promising young and ambitious male and female politicians who seem poised to occupy high positions in important countries; the elite wants to ensure that these rising stars of the political firmament may be counted on to defend and promote the interests of the elite.

In 1991 and in 1993, respectively, Bill Clinton and Tony Blair thus presented themselves at Davos to be “anointed” by the cardinals of the world’s business and banking. The elite consists of extremely wealthy people, and it is not too fanciful to describe them as the “1 percent” of the world’s population who own the bulk, possibly 99 percent or even more,of the world’s total wealth. Because of its wealth, the elite enjoys enormous power. It is indeed a power elite, but in general its members do not involve themselves directly in politics.

They prefer to remain behind the scenes, leaving the political work to be taken care of by reliable leaders of reliable political parties — in other words, by personalities like Clinton and Blair; and these are frequently women and men of relatively modest social background, who are therefore not easily perceived to be members — or acolytes — of the elite. This is a sensible strategy within the context of political systems that purport to be democracies, that is, systems that are supposed to serve the entire “people,” in other words, not the privileged 1 percent but the mass of ordinary citizens, whose interests are often very different from those occupying the apex of the social pyramid.

One should not conflate the plutocrats of big business and finance, the true capitalists, with petty business people such as the owners of small companies and self-employed “entrepreneurs.” Small businesswomen and businessmen do not feel at ease in high society. They do not belong to the upper class, but to the middle class or, to be more precise, to what sociologists label the “lower-middle class.”

The term “upper-middle class,” on the other hand, is used by sociologists and historians to refer to the industrialists and bankers (and some other categories of very wealthy individuals) who, during the nineteenth century, joined — and sometimes even supplanted — the aristocrats, that is, the original “upper class,” at the top of the social hierarchy. Earlier, the elite had indeed been monopolized by blue-blooded types ranging from monarchs down through dukes and counts to barons and other lesser landowning lords of the type portrayed by the protagonist of the TV series Downtown Abbey.

The men and women of big business and finance who joined the nobility at the apex of the social pyramid are sometimes also designated à la française as the “haute bourgeoisie,” while small businessmen and businesswomen are said to be part of the “petite bourgeoisie,. where they rub shoulders with artisans, shopkeepers, schoolteachers and others like them. Below the level of this petty bourgeoisie, at the broad base of the social pyramid, we find the mass of wage-earners, that is, those who contribute their labour to the production process and receive a wage in return.

In the past, and certainly in the nineteenth century, this referred primarily to workers, and more particularly, factory workers. These days, however, the term worker is hardly used, and not only because it conjures up unpleasant things such as low incomes, polluting factories and strikes; an even more important reason is that the semantic elimination of the terms worker and working class has automatically promoted all wage-earners to the middle class. It should be acknowledged, however, that since the end of the nineteenth century many workers; the so-called labour aristocracy, have managed to achieve high wage levels and have therefore arguably achieved petty-bourgeois status.

Doing business is about making profits, and the alpha and omega of big business is to achieve the highest possible profit levels, in other words, to maximize profits. To realize this “ideal,” the people of big business (and finance) are prepared to go to great lengths. As individuals, they may be kind, less kind or not kind at all, but that is of no importance whatsoever. Kind or not, the laws of business require them to be tough, even very tough. If they are not, they will not survive in the “jungle” that the world of business happens to be. (As the saying goes, nice guys finish last!).

One must be ruthless to be able to produce the high profit levels that happen to be the ultimate objective: competitors need to be eliminated, workers and other employees must be driven to work harder and must often be fired, wage levels must be lowered while prices must be increased, and so forth. Even if one does not want to do this, one must nonetheless do it; otherwise, someone else might do it and thus gain a competitive advantage, causing you to achieve lower profits and perhaps even force you out of business. As for the human misery that is caused in the process, one learns not to worry about it: profits have priority over people. That is the way things work in the world of big business, in other words, in the socioeconomic system called capitalism.

However, the intellectual apostles of this system do their very best to persuade us that it is the only possible socioeconomic system, and that there is no alternative. The history of capitalism shows that the women and men of big business can feel comfortable in a “democratic” political system or “state,” at least when it proves possible to achieve sufficiently high profit levels within such a political context. However, if they convince themselves that sufficiently high profits can be generated only when the state is run by a “strong leader,” that is, within the framework of a dictatorship, they reveal themselves ready and even eager to help to bring a dictator to power.

We say “help to bring to power,” because other social actors may likewise be prepared to lend a helping hand, for example large landowners, aristocratic or not, prelates of the church, and army commanders. A democracy is supposed to permit the majority of the population, the ordinary citizens referred to as the demos in Greek terminology, to participate — most typically by means of fair elections — in the political life of the nation. But that is not all.

A democracy is also expected to enable all citizens to enjoy a decent standard of living, and this entails the enjoyment of a wide range of social services (such as education and health care) as well as the opportunity to work for a fair wage. Businessmen and bankers are prepared to bear a share of the cost of such services and to pay their workers relatively high wages if they can maintain a level of profitability that is high enough from their perspective; and they prove quite willing to make such concessions when not doing so threatens to provoke unrest, protests, riots and — above all — revolution, because that would mean the end of their wealth, power and privileges.

However, if the cost of wages and of their contributions to social services rise to such an extent that the profitability of corporations and banks is jeopardized, the owners and managers are ready to do whatever is necessary to lower wages and eliminate social services.

Like everybody else, the men and women of big business are devoted to the ideal of “peace on earth,” at least if peacetime conditions allow for sufficiently high profits to be made. But when it appears that higher profits can be achieved by means of war, they do not hesitate to worship Mars, the more so since the dirty work involved is virtually always left to others; the killing and dying is indeed usually delegated to the masses of the lower classes, hoi polloi (literally, “the many”), considered too numerous and therefore restless and dangerous, so that a little “culling” is deemed permissible.

As Jean-Paul Sartre aptly stated: “When the rich wage war against each other, it is the poor who die.”

So far, our discourse has been relatively abstract. However, historical examples can be adduced in every case, and this study focuses on one such example. We have examined the attitude of the industrialists and bankers of Germany, the United States and some other countries vis-à-vis Adolf Hitler and his national socialism (or Nazism) and fascism — of which Nazism was the German version — in general.

The capitalists of these two countries rushed to do business with Hitler, and both sides, the industrialists and bankers on the one hand and the Nazis on the other, derived considerable benefits from this collaboration. The advantages obtained by the industrialists and bankers happened to be exactly what they had dreamed of: unprecedented profits.

As an example, we can cite here the case of IG Farben, a trust composed of Bayer, Hoechst, BASF and other big firms. This enterprise which supported Hitler’s rise to power, was deeply involved in his armament program and, during the war, made a fortune by (ab)using slave labour in all its factories, and above all in a gigantic facility located next door to the sinister extermination camp of Auschwitz.

American capital likewise supported Hitler at an early stage, even though it is not yet clear to what extent. And it also achieved enormous profits by producing an array of weapons and other war materiel for the Nazi regime in the numerous German branch plants of American corporations and by supplying colossal quantities of fuel, rubber and other strategic raw materials to the Nazis. Without these American supplies, Hitler could never have unleashed his murderous Blitzkrieg, his “lightning war.”

During the war, and even after Pearl Harbor, America’s big business continued to be involved in major deals with Nazi Germany. Colossal profits were thus achieved — and maximized by the use of forced labour, including deportees from the occupied countries and even concentration camp inmates. As an example, we can refer to the case of Ford, the family business of Henry Ford, a widely admired American icon who also happened to be as anti-Semite as Hitler himself.

Ford made a fortune by supplying Nazi Germany with trucks and a wide range of war materiel; some of this was exported from the United States, but the bulk was produced in Ford’s subsidiary in Cologne, known as the Ford-Werke, the “Ford Works.” The profitability of Ford’s German investment received an extra boost during the war thanks to the use of slave labour.

The Kamikaze: Pearl Harbour bombing of US ships by the Japanese suicide bombers in 1941

Germany’s as well as America’s industrialists and bankers did wonderful business with the Hitler regime. And at the same time, they did wonderful business with each other, reaping kingly profits in the process. It is only natural that they wanted to continue doing business with each other after the war, after the demise of the Nazi regime they had collaborated with until its very end.

However, to make that possible it was necessary to wash away the Nazi sins of Germany’s big industrialists and bankers. And that turned out to be possible because the major decision makers within the American government in general and the American occupation authorities in Germany in particular happened to be representatives of America’s big enterprises and banks. By forgiving and forgetting the collaboration of Germany’s capitalists with the Nazis, America’s capitalists simultaneously forgave, and obfuscated, their own highly profitable but essentially criminal collaboration with the Nazis.

Germany’s industrialists and bankers supported Hitler during his rise to power and made gigantic profits thanks to his socially regressive policies, his armament program and the war he unleashed. America’s big industrialists and bankers likewise provided support to Hitler during his ascent, and the profitability of their enterprises too was maximized thanks to the typical initiatives of the Nazi regime. But American capital also benefited financially from the war Nazi Germany fought against Britain, the Soviet Union and finally — because of Hitler’s own fault — the United States itself.

Never had America’s corporations been able to make as much money as they did during the Second World War, namely by supplying — not donating, as is sometimes suggested, but selling, often at inflated prices — to all belligerent countries, Germany as well as America herself and her allies. Hitler’s Nazism, and fascism in general, had been profitable for America’s capitalists. That is why, after 1945, they continued to be fond of fascist (and other) dictatorships such as those of Franco, Suharto and Pinochet.

However, in the final analysis the war had performed even better for capital than fascism had: it had revealed itself to be a horn of plenty, bestowing fabulous profits on the big enterprises and banks of the United States. America therefore continued to wage war after 1945, has continued to do so even recently under a president with a Nobel Peace Prize on his CV, and is unlikely to cease worshipping Mars soon. If peace ever descends on earth, it would be a catastrophe for America’s big business.