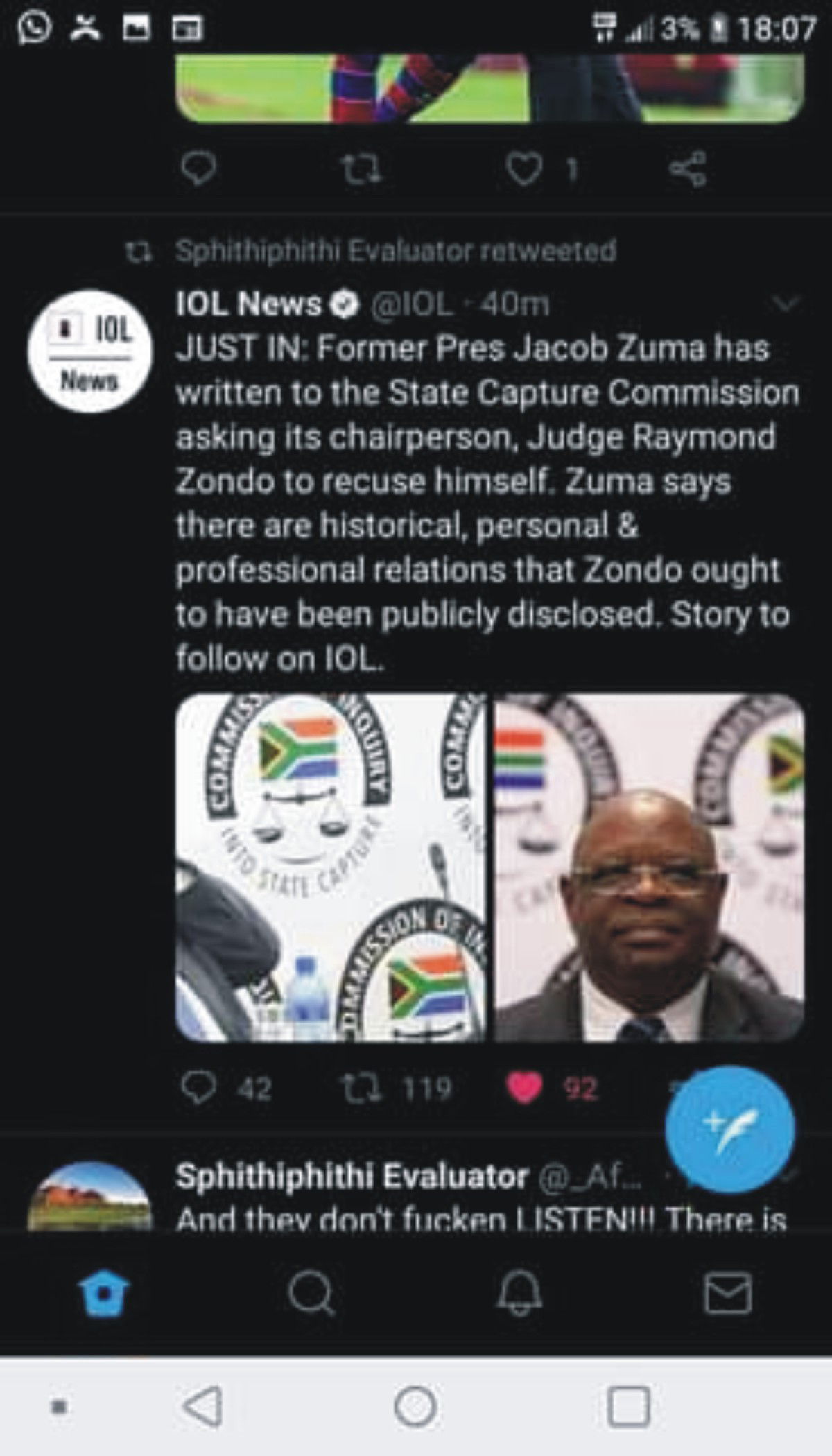

DCJ Raymond Zondo is breaking the law by trying to force Zuma to testify in his Commission: Adv Vuyani Ngalwana SC, who also occasionally act as a Judge of the Supreme Court

By Adv. Vuyani Ngalwana

[Side Note: Advocate Vuyani Ngalwana lays bare a series of the comedy of errors that has unfolded in the so called State Capture Commission of Inquiry to render it invalid from the outset as no truth seeking Commission but a barefaced witch-hunting expedition.

Zondo seems to know that witnesses can not be forced to testify in the Commission when it comes to his ignorance of Pravin Gordhan’s belligerence to appear before the Commission, yet he doesn't miss an opportunity to call a Press Conference to threaten with summons those that he is targeting like former President Jacob Zuma.

In a healthy democracy; Deputy Chief Justice Raymond Zondo would not only recuse himself, but he would also lose his license to practice both as an attorney and a Judge as he has not missed an opportunity to put the South African judicial system into disrepute from the word go of the so called State Capture Commission of Inquiry.]

With the proliferation of Commissions of Inquiry in recent years in South Africa there appears to be much confusion among consumers of news as regards what exactly the purpose of these things is.

Allied to that is the confusion about what the role of evidence leaders in Commissions of Inquiry is and that of the media in its coverage and analysis of Commissions of Inquiry. This opinion piece seeks to answer each of these questions based on the experience that the author has had with Commissions and other similar interventions.

The point made in the opinion is this: a Commission of Inquiry is not a court of law. Rules of evidence do not apply as strictly as they do in a trial court. The Commissioner does not make judgment; s/he makes recommendations which are not binding on the President.

There are no accused persons, prosecutors, defence teams, convictions or acquittals. Every witness must be treated the same by evidence leaders and by the Commissioner. Talk of cross-examination in a Commission of Inquiry is inappropriate. This opinion piece is intended to help the reader think more critically about what s/he reads in the media about the goings-on at Commissions of Inquiry...

Mulder 1980 (1) SA 113 (T) and S v Sparks NO and Others 1980 (3) SA 952 (T); Bongoza v Minister of Correctional Services and Others 2002 (6) SA 330 (Tk)]. But this does not provide license for the manufacture of facts through “opinion” pieces or “analysis” served up for a predetermined purpose intended to sway public opinion.

That is why it is particularly important, for the sake of the integrity of the Commission of Inquiry and its recommendations, that facts that are presented at the Commission are carefully verified before they are presented, not after they have already taken root in the psyche of the public. Thus, verified rather than verifiable evidence is preferable.

There are a few key role players who could affect the effectiveness of a Commission of Inquiry. Here I touch on the evidence leaders, the Commissioner, the media and analysts.

Evidence Leaders are not the Commission of Inquiry. They are appointees of the Commission of Inquiry. The Commissions Act in South Africa makes no provision for the appointment of evidence leaders. So, there is no requirement in the controlling legislation that an evidence leader must be appointed to a Commission of Inquiry.

Regulations of the “State Capture” Commission confer upon Deputy Chief Justice Zondo, the Chairman, the discretion to “designate one or more knowledgeable or experienced persons to assist the Commission in the performance of its functions, in a capacity other than that of a member [of the Commission]”. These are the evidence leaders, the investigators and any other persons whose skill the Chairman may require.

[Side Note: So it is Justice Raymond Zondo who appointed the controversial Adv. Paul Pretorius to lead the evidence against former President Jacob Zuma, the same advocate that ultimately strayed into the grey area of cross-examination without a mandate to do so; according to objections by Zuma’s legal Counsel last year]

Overstepping his boundaries without a reprimand from Judge Raymond Zondo: Behind the scenes their roles might be reversed, with Pretorius being a real Chair of the Commission and Zondo his evidence leader

Facts given in evidence at a Commission of Inquiry should ideally already have been verified by evidence leaders (where appointed) in order to avoid evidence that may be tailored for purposes other than the search for the truth. This would save both time and money because (1) it will not be necessary for a witness to be recalled for “cross examination” some weeks (if not months) after her initial evidence and (2) any “cross examination” by counsel for those implicated by the witness will most likely be limited because the evidence leaders would already have verified the facts to which the witness testified.

A search for the truth does not entail an attack by evidence leaders on witnesses. In fact, such attack tends to have the opposite effect to attaining the truth. Having managed to get a horse to the river for a drink, try forcing it to drink and see how far you get. Nowhere. An aggressive and hostile questioning of a witness by an evidence leader is counter-productive.

Thus, all witnesses must be treated equitably and fairly. It is not the role of evidence leaders to “lead” some witnesses in evidence, asking them rehearsed sweetheart questions, and “cross-examine” other witnesses. In fact there is, strictly speaking, no room in Commissions of Inquiry for “cross-examination” because that is language that is associated with a trial or other formal court process.

Witnesses in a Commission of Inquiry are questioned, not cross-examined. Cross-examination is a special form of questioning that is governed by its own rules, conventions and ethical standards. It is best performed by professionals trained in the science or art of trial advocacy. Witnesses at Commissions of Inquiry should not have to be put to the expense of hiring experienced advocates to have the evidence of those who implicate them tested. If evidence leaders do their job properly, this should not be necessary.

Because the ultimate aim of Commissions of Inquiry is a search for the truth, witnesses often meet with evidence leaders privately, before giving evidence in the open, so that evidence leaders can assess the evidence, test it against facts and other evidence already in their possession, and have it reduced to writing. There should be no room for surprises, whether on the part of evidence leaders or on the part of witnesses.

During the Marikana Commission, for example, the evidence leaders interviewed the police witnesses they wanted to interview before those witnesses gave their evidence in open session. On that approach, nothing that the witness says in evidence can come as a surprise, unless the witness changes his or her evidence while giving oral evidence at the hearing. It is thus unhelpful to the cause of a Commission of Inquiry for evidence leaders to behave like a prosecuting team in a criminal trial. Evidence leaders have no witnesses of their own. They should thus have no “version” to put to witnesses for “cross examination” purposes.

Evidence leaders should also be particularly careful of treating media reports and opinion pieces as evidence. They are not. They are simply information to be assessed and tested against other available information. They do not constitute “a version” to be put to witnesses. This should not be difficult to understand because a version can only be tested by questioning the witness advancing such version.

A related concern is the belief that witness (B) who comes to the Commission voluntarily in order to correct a factual account given by witness (A) about witness (B) in the physical absence of witness (B) must first agree to subject herself or himself to cross-examination on matters that travel far beyond what witness (B) came to the Commission to correct. That approach is in my view an ambush.

Worse still, witnesses could be flushed out into the open through other witnesses deliberately telling untruths for the sole purpose of compelling the implicated persons to come forward and be questioned on matters that tend to embarrass third parties so that those third parties can also in turn be flushed out into the open. Such testimony by ambush is undesirable and inconsistent with the purpose of a Commission of Inquiry.

The Commissioner

Evidence leaders perform the functions that would otherwise have been performed by the Commissioner. In a sense, the evidence leaders are an extension of the Commissioner’s ears, eyes and brain. That is why the Commissioner is free, at any time, to interrupt the questioning of a witness and ask the questions that s/he wants to ask in the manner and tone that s/he prefers to ask them.

The Commissioner is free, at any time, to redirect the focus of an inquiry into a witness’s evidence, or even take over the questioning altogether. This is not an adverse reflection on the ability or proficiency of the evidence leader who is questioning the witness at that time. The Commissioner must be independent, impartial and dispassionate in the search for the truth. This necessitates an astute awareness of potential undue political influence, personal biases as well as the impact of the direction taken.

This includes the conduct of the Commissioner, which could have far reaching implications. It would, for example, not be appropriate to have legal representatives of a person implicated in evidence given in his absence attacked by the Commissioner. The personal attack on Counsel by the Commissioner in the Nugent Commission was, in my view, regrettable and highly inappropriate. Even courts seldom criticise Counsel’s approach in the presentation of his client’s case as acerbically as did the Commissioner in the Nugent Commission, describing it as “a disgrace”. It does not help lay bare the truth.

The High Court subsequently pulverised Counsel’s approach but then the High Court was sitting in judgment of a case, not as a Commissioner in a Commission of Inquiry. Whether the Judge did so justifiably or not the Constitutional Court will decide as I understand that the matter is now pending for argument before the Constitutional Court.

It is in my view, wherever practicable, advisable to have a Commission of Inquiry comprising a panel, so that other panellists may conceivably help reign in an over-zealous Commissioner who might, by her or his conduct or unguarded utterances, open the proceedings up to the risk of a successful review challenge. Of course, this approach does not take account of an overbearing Commissioner or supine panellists.

A Commissioner should not play the role of a Judge in a trial. His is rather the role of a Mediator than a Judge. This is because what is expected of him at the conclusion of the hearing is not a judgment but rather recommendations. Like a good Boxing referee, he should rarely be noticed, especially when there are evidence leaders around doing a proper job.

[This means Justice Raymond Zondo’s final verdict on State Capture Commission will not be a judgement but rather recommendations - Ed]

As the Commission is not about the Commissioner, he should avoid becoming the news. The news in relation to a Commission of Inquiry should be the evidence that was given, not the Commissioner.

The Media’s Role

Talking of news in relation to Commissions of Inquiry, informing the public about these matters is a task that one would expect the media to perform jealously. After all, the Constitution itself in Section 16 confers upon the media the fundamental right to “impart information” to the public.

The media did that, largely successfully and impartially, during the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. But the discerning ear may find the media coverage of the Marikana Commission and the “State Capture” Commission, for example, characterised by imbalanced reporting of extraordinary proportions as some witnesses were (and are) condemned not so much for what they say as for what they are perceived by the media to represent, while other witnesses, by the same measure, have their perceived virtues extolled and their glaring shortcomings either redacted or completely eradicated.

During the Marikana Commission, public sentiment lay unmistakably with the victims of police shootings and less so with the victims of the workers. It is not difficult to understand why this was so. But media coverage of those proceedings contributed in no small measure to that result and, most probably, contributed to steering the expected outcome in a particular direction.

In contrast, the Marikana Report itself apportions some responsibility to all participants in the events of that fateful week. The blame apportioned to the strikers was based on evidence that was led at the Marikana Commission by numerous witnesses. But one would struggle to find media reporting of that evidence, which could lead to the conclusion that many in the media had already decided that the police were “guilty” and trigger happy.

Those of us who gained intimate knowledge of the facts by legally accepted and scientifically recognised forensic methods came to understand the complexity of those events.

The subsequent finding of the Marikana Commission in its Report, that it “does not believe that it would be appropriate to draw an adverse inference against all those [who] fired their weapons at scene 1” and that “some [police] in all probability did not exceed the bounds of self and private defence”, appears not to have made much difference to some in the media to report more accurately on the evidence presented. In fact, this was the police’s main defence which the media generally ridiculed at the time it was presented at the Commission.

This is not becoming of journalists who are supposed to “impart information” to the public fairly, impartially, independently and with neither fear nor favour. A journalist should not present an opinion as fact. The right to “freedom of artistic creativity” in Section 16(1)(c) of the Constitution does not extend to playing artistic creativity with facts.

[Side Note: Regular South African media houses do not acknowledge this disclaimer that when you write a hard news story as a journalist you are not actually telling a fact but reporting on allegations. That’s why Press Code Section 1.8 of the Press Council of South Africa stipulates that both sides of the story must be heard before a news article is published except where it is stated clearly that an article is an opinion piece. So what you regularly read about as news is basically allegations from certain sources and respondents; finish and klaar – all allegements from parties involved in a news story.

Except for rare and investigative cases where a journalist was at the scene when the story unfolded and perhaps was an eye witness who recorded the incident or perhaps a source provided the journalist with tangible evidence to the allegation; e.g emails, transcripts or telephone correspondence as fact. There is one publication one could vouch for that gathers facts and evidence before it publishes its news articles as factual; that is Noseweek. But most of what you read about in the regular newspapers as news is a matter of somebody who said something about somebody and another party responding to those allegations. Allegations most often than not passed as holy truth by the mainstream media to enhance sales of their publications].

The role of the media in Commissions of Inquiry is not to take sides as there are no sides to be taken in a Commission of Inquiry. Everyone is on the same side: the side of the truth. The role of the media is to report the facts, based on the evidence being presented by all witnesses, not air-brush a favoured witness’s flawed evidence and decontextualize an honest account by a witness already condemned for what s/he is perceived to represent.

This is what seems to have happened thus far in the media coverage of the “State Capture” Commission. One cannot but wonder whether some witnesses are championed by the media, while others are vilified. One sees, for example, evidence of a witness being reported as having “set the record straight” before his evidence has even been tested by evidence leaders or those it implicates. One wonders what the headline will read if that “record” is sent down a crooked path by a rudimentary testing of its contents.

Journalists should report the facts as articulated by the witness. The moment the journalist introduces “motives” for the evidence in her reporting, or starts “joining the dots” to arrive at a well-constructed theory of the evidence, she is no longer imparting information. She is giving judgment and, worse still, making it difficult for the Commission to perform its work impartially, independently and without fear, favour or prejudice.

The danger of journalistic opinion masquerading as fact is that the public may in the end find it difficult to reconcile the findings and recommendations of a Commission with the “findings” of an ill-considered journalist-cum-analyst, and reject the Commission’s findings. This is dangerous and may have adverse effects on the Rule of Law. The Rule of Law is endangered if journalists play fast and loose with the facts and evidence presented in a Commission of Inquiry.

In short, journalists who put their opinions ahead of the facts given in evidence at Commissions of Inquiry do more harm to the process of truth-finding than good.

What of instances where a journalist puts up material in a media publication that is relevant to the subject-matter of the Commission but refuses to have it tested under questioning by evidence leaders in the open, on the ground that she cannot be compelled to reveal her sources?

For example, what is the “State Capture” Commission to do if a journalist were to claim in an article to have information that, say, a judge of the Constitutional Court has been in gainful partnership with the Gupta brothers for over a decade for the supply of, say, military equipment to the SANDF without a tender, but the journalist refuses to be questioned on that information by the Commission?

Such a scenario is not altogether far-fetched. In September 2003 a journalist claimed that then National Director of Public Prosecutions was an apartheid spy. When called to give evidence at a Commission of Inquiry established by the President to search for the truth of that claim, the journalist refused, challenged the invitation in court, lost, applied for leave to appeal and, while that was pending, the Commissioner decided to excuse her from giving evidence as he considered it not worth the delay.

The Commission ultimately found that the claim was false. But what if the truth or otherwise of the claim lay only in the testing of the journalist’s evidence by questioning her in open session at the Commission?

Journalists in South Africa seem to believe that they can never be compelled to answer questions at a Commission of Inquiry (or a court) on the subject of their story, whatever the circumstances. This is incorrect. A journalist can be compelled to testify unless to do so would infringe upon his or her constitutional right or freedom unjustifiably. But whether compulsion would infringe upon any such right or freedom depends on the nature of each question, and can become clear only when the question is put (see Nel v Le Roux 1996 (3) SA 562 (CC) at para [7]).

There is in our law no general absolution of journalists from answering questions about their story in a Commission setting. Freedom of the press and other media does not provide license to a journalist to spread a false narrative about people, and then hide behind the sanctity of sources and press freedom.

The media in South Africa has some serious introspection to do in its coverage of Commissions of Inquiry. There are too many instances where it appears that some journalists have become emboldened to mount vitriolic attacks on judges personally for making judgments that the journalist does not like or with which the journalist disagrees.

Take the case of Jiba and Another v General Council of the Bar of SA and Another; Mrwebi v General Council of the Bar [2018] 3 All SA 622 (SCA) for example, in which the Supreme Court of Appeal found that the conduct of the two appellant advocates did not deserve ultimate censure of being struck off the roll of advocates. A journalist, writing for Daily Maverick, so personally and trenchantly attacked two judges of the Supreme Court of Appeal in July 2018, effectively associating them with corruption at the highest level of government, that the General Council of the Bar of SA, the party on the losing end of that judgment, was moved to issue a media statement condemning the attack.

If judges can be so wantonly attacked by a journalist just because the journalist does not like the judgment, what hope does a Commissioner have in a Commission of Inquiry when issuing a report containing recommendations that are inconsistent with the narrative already carved out by journalists for an outcome favoured by them? Should the Commissioner wait until then, in the hope that the General Council of the Bar will condemn the attack, or should the Commissioner be given statutory powers to nip this undesirable and inappropriate practice in the bud?

What deterrent effect does an ex post facto condemnation of such personal attacks on judges have? I have not seen any.

Analysts

There is another burgeoning phenomenon in South Africa: that of “a political analyst”. The South African variety is difficult to place as the same person could one day be a radio talk-show host, a television show host the next, an analyst the next day, and a journalist when called for. Most striking is that the “political analyst” is often readily identifiable with one political narrative and leader, pushing that leader’s line at every opportunity, and exhibiting unmasked hostility towards another political narrative and leaders, excoriating them at every opportunity.

Such “a political analyst” poses a greater threat to a Commission of Inquiry because, as she is no “media” or “press” when wearing the “political analyst” hat, the media regulator can arguably have no power over her for misrepresenting facts given at a Commission. When posing as a hired gun, she can snipe with impunity at witnesses who present evidence that is unfavourable to her favoured politician or narrative.

What is the Commission to do in such circumstances: Issue a warning that such exploits “obstruct the Commission in the performance of its functions”, which the Commissions Act proscribes, or “prejudice the Inquiry”, which the “State Capture” Commission regulations prohibits, and so constitutes a criminal offence?

Conclusion

Since the purpose of a Commission of Inquiry, like the “State Capture” Commission, is truth-seeking, every participant in the proceedings of the Commission – from the Chairman to the evidence leaders to the witnesses to the lawyers representing witnesses – must have one single purpose in mind: assist the Commission to get to the truth and nothing but the truth.

Commissions of Inquiry, when properly used for what they are intended, are an important feature of the Rule of Law. If everyone plays his or her role as it should be played, Commissions of Inquiry are an effective tool. If abused by even one of the role-players discussed above, Commissions become expensive, inconsequential pursuits fit only for the settling of political scores. No judge would enjoy being used as a pawn in a political Chess game.

Unless Commissions of Inquiry are used for what they are intended, increasingly fewer judges of integrity will avail themselves for them. In the end they will be discredited, along with the Judges who preside over them.

A practising advocate and Senior Counsel; Adv. Vuyani Ngalwana SC has previously served as the Pension Funds Adjudicator, Deputy Director of Public Prosecutions: Asset Forfeiture Unit as well as Chair of the Council for Medical Schemes Appeals Committee

source: anchoredinlaw